This is an article that appeared in SFQ (Silent Film Quarterly), Volume 1, Issue 3 ~ Spring 2016.

COMING ATTRACTION Slides

Coming Attraction slides are forerunners to the familiar trailers shown in cinemas today, before the start of the feature. In the general term of a slide most people are probably more familiar with the 35mm variety, of the more recent past and today, rather than the slides used to advertise forthcoming feature films, and shorts, during the silent era.

The actual history of the slides themselves, is quite storied. Not just something recent, as known, or associated with either the film company Eastman Kodak, or from school lectures. The first slides and projector was invented by a mathematician, inventor and Jesuit priest named Athanasius Kircher (1601-1680). His invention was called a ‘magic lantern,’ and projected so-called ‘magic shadows’. The first projector and projection of slides happened in 1644, or 1645. Kircher detailed his invention and discoveries, in 1646, in his publication Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (“The Great Art of Light and Shadow”).

Not just Kircher, however, many other thinkers, scientists and inventors helped to further studies and develop slides and other magic shadow apparatus, over the next 250 years into the development of the film we have today. The projected films of Auguste Lumiere, in 1895, in France, and the subsequent April 23, 1896 presentation at Koster & Bials’ Music Hall, in New York City are legendary, as well as famous.

While films of the silent era were projected onto the cinemas’ screens for audiences to enjoy, exhibitors needed a way to entice the cinema-goer back into their theaters – the following days and weeks – for the latest films. While advertising with posters, lobby displays and newspapers helped, these were the days before radio and television. Cinema managers needed another form of advertising to capture their audiences. For this they used a magic lantern slide format which were, aptly called, “coming attraction” slides.

Lantern slides prior to the advent of photography were pictures traced onto glass and hand painted. Later transfers, similar to decals, were used. When the photographic process was adapted the ability to transfer photos as transparent positives brought a new dimension to the art of projected slides.

These photographic slides consist of two sheets of glass – one that bears the photographic image; the other, is a protective cover over the emulsion of the first. These two sheets of glass were separated by a black paper frame masking. The whole slide was then bound along the four edges by gummed fillets of heavy black paper tape. The slides were generally 3 1/4 inches high by 4 inches wide. Although, the sizes varied by some countries; for example, in England they measured 3 1/4 inches square. Later slides, circa 1924, consisted of only the emulsion image sheet of glass, which was inserted into a three-fold cardboard masking border/frame. A larger version of the standard 35mm slide.

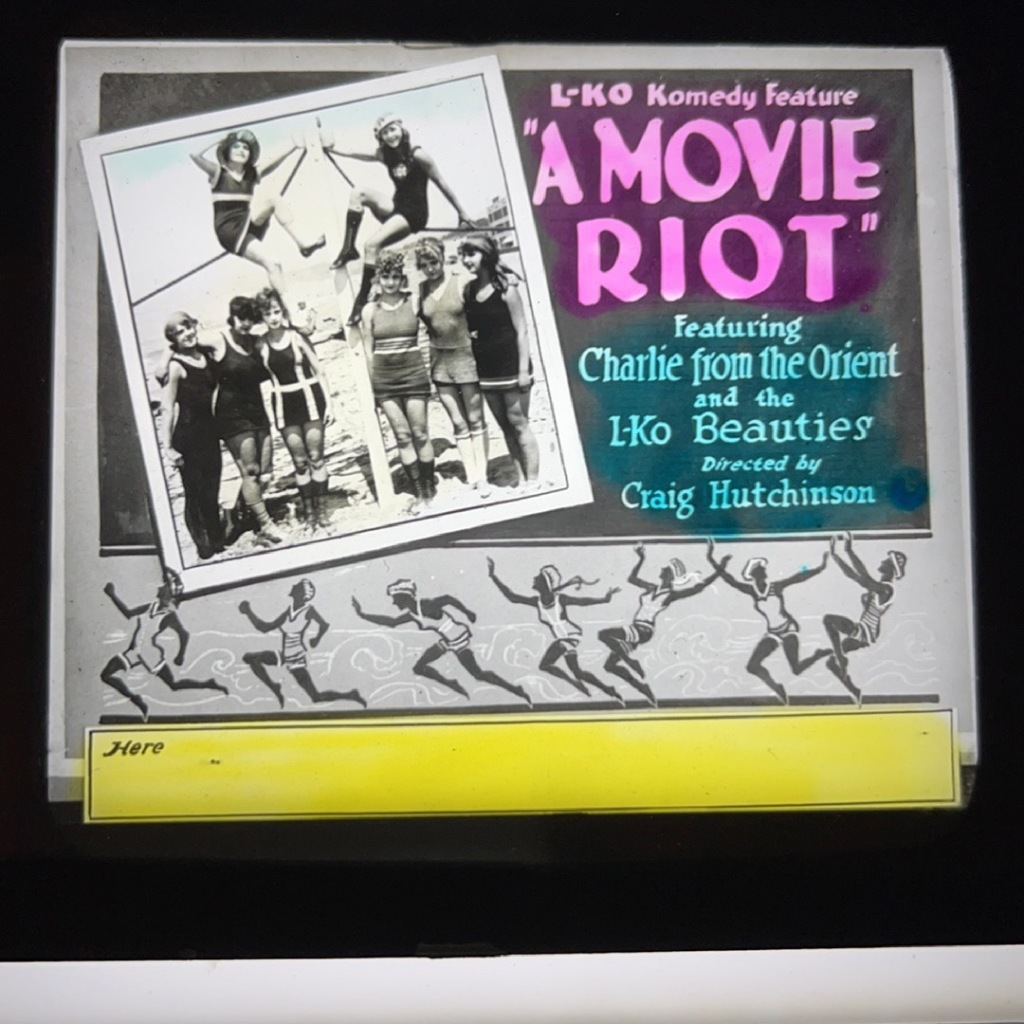

While the films advertised with the coming attraction slides were generally presented in Black & White, the slides themselves were usually hand-tinted, or painted to add a ‘pop’ of interest to scenes depicted on the slide. Other information on the slides could include credits (such as producer, director, writer, or story based on, on in some instances stars’ names). Along the bottom edge of the slides was a narrow blank border space, known as a “here” area, wherein the manager or projectionist would write in India Ink the scheduled day/date the film would show at the cinema. A companion to the coming attraction slides were trade advertising slides, similar to today’s commercials, these were also known as, ‘Public Service’ slides. Also, song slides, of current day popular songs were projected during the Intermission.

Silent films have been seeing new and increasing audiences through film festivals, DVD releases, and film restorations, as well as, recent film releases like “Hugo” and “The Artist.” Yet, with all the new found fascination of silent films, it remains a simple fact that films, especially silents, are vulnerable. It’s estimated that 80% of all silent films are lost.

Sometimes, as I’ve found out through research, these slides are the only instance we have of a particular film’s history. As is showcased with the illustrations in this article, even these slides are painful reminders of the fragility of film, and help make the case for preservation of , not just, silent films but all films as preserving our cultural heritage.

An interesting article in the Los Angeles Times, dated August 17, 1928, shows that coming attraction slides were fast being replaced by trailers, and even more so with the advent of talking pictures. Slides – which used to get audiences to settle into their seats and relax – were now getting audiences excited, as exampled “when Conrad Nagel, appeared on the screen in his talking trailer for the present picture ‘Lights of New York,’ he received a round of applause.” Slides were still used in many cinemas up to and through the 1940s, and in some instances, even the 1950s and 60s. However, the coming attraction slide generally met it’s overall demise during the early 1930s.

Coming Attraction slides were manufactured in mass quantities by numerous companies, as well as, the studios themselves. These slides were the property of the studio producer, or distribution company, and rented by individual cinemas, along with posters (one-sheets, two-sheets), including lobby displays. Said items were supposed to be returned after the run of the film ended, to prevent unauthorized use. However, because the slides were glass and fragile, many were often not returned, and either trashed, or stored somewhere in the cinema.

In certain instances, you would see a slide where an enterprising manager or projectionist (of smaller theaters) would scratch off the old title and the latest title release inked in, especially in the case of major stars, with their face pictured on the slide.

THE BRENKERT F7 MASTER BRENOGRAPH LANTERN

The slides in many cinemas would have been projected onto the screen by the Brenkert F7 Master Brenograph Lantern, or projector, manufactured by the Brenkert Light Projection Company of Detroit, Michigan.

The projectionist with this projector/lantern would have been able to project images anywhere on the stage or throughout the cinema auditorium. Any shape, size, color, or focus of animated or stationery images, except motion picture film – the varieties of images limited only by the imagination of the projectionist.

The Master Brenograph had two lantern housings – both upper and lower, were coupled together in every way; however, both systems could be operated independently – only the fader – or iris dissolving shutter, in upper and lower units were linked in unison.

The F7 model projector consisted of the upper and lower projection lanterns, each with a lamphouse that held 75 ampere vertical feed carbon arc burners; the shutter and effects holder, framing shutters, a mask compartment for screen borders or special masks, effect holder for design plates, animated scenic effects and stationary color frames. Then, the slide carrier – adaptable for 4×5 inch slides, or the standard U.S. size of 3 1/4 x 4 inches, or an insert for U.K. English slides of the 3 1/4 inch square variety.

Standard Slides: were those for cinema advertising such as the coming attraction slide for forthcoming features, or local advertising from merchants in the neighborhood promoting their stores‘ wares or business services.

Dissolving sets made in themed pairs, measured 5 x 4 inches and were a positive and negative image, with a color filter for the various outlines or shapes produced sophisticated changing scenes, with up to twelves slides to create anything from sunsets, haloes, colored clouds, or other atmospheric effects, again the only limitation being imagination. The Majestic collection produced for the Master Brenograph contained approximately 300 pairs and 120 sets in color, allowing projections of simple geometric patterns to more complex scenes, and illustrations.

Glass Design Slides: consisted of a pane of glass that could distort the image(s) or color effect(s).

Animated Scenic Effect Slides: these slides were unique, looking more like a movie film reel canister, with a clockwork mechanical drive. Inside the container was a mica, hand painted sheet chosen from a large number of varied designs.

These were used in the effects holder, and once in place the operation of the switch the mica disk would rotate and the image appeared on the screen moving either left to right, up and down, or down and up, even diagonally, at one pre-set speed. Designs on these mica disks consisted of clouds, auroras, falling snow, rain, birds, fish, waterfalls, or shooting stars. Even two separate disks, one as a landscape in daylight, another sunset, when combined with a train panorama slide – the ensuing dissolve effect makes it seem the train is traveling across the countryside during the day into evening.

Panorama Slides: as mentioned above, measured 18 x 5 inches. Other slides could represent an evening view of the city skyline, with skyscraper windows all lit up, or a photograph of the Louvre museum, in Paris.

Two separate carriers were used for the slides; one operated manually or by clockwork, the other electrically operated. Blending Color Wheel and Gelatin Color Frame Holders. The wheel was, again, clockwork driven, and produced a rippling effect of color on the screen.

Other typical accessories for mastering effects included a Star Shutter or Lobsterscope. The Star was an adjustable diaphragm in a star shape pattern, and could be projected onto curtains or the organ console, producing “charming effects.” While the diaphragm of the Lobsterscope had a shape, or effect, similar to an “opening eye.”

The Brenkert was primarily a projecting lantern, but was also often used as a spotlight, much like a follow-spot. Depending on the projectionist, the combination of slides and effects, could transform a movie-going audiences’ evening entertainment from ordinary to stupendous. I can only imagine how pleased Athanasius Kircher was with the latest modifications of his original magic lantern, circa the 1920s.

COMING ATTRACTION Slides as Collectibles

Collectors usually collect a plethora of items pertaining to their likes or favorites. And, when it comes to those who collect movie memorabilia – it’s no different than sports fans or toy collectors, to name just a couple. Most collect a favorite star or two (maybe more), or films in a specific genre, or studio. And, of that star or genre or film, it’s paper, or books on a shelf about the subject, or posters and photos on a wall, or possible trinkets on a table or shelf. When it comes to collecting Coming Attraction slides, they are small, but made of glass. Therefore, far more delicate to both store and admire. And, no easy way to showcase unlike framed posters, photos and autographs, or stacked like books on a shelf.

I began to collect slides, quite by accident, almost twenty-five years ago, having collected just about everything else (books, posters, photos, autographs and most other ephemera). From my first hesitant purchase of nearly seventy-five slides, today, the collection has grown to nearly 2,000. They are numerically stored and cataloged, by the slide’s number, assigned by me, as I acquire them. They are also entered into a computer database, formatted by me, that I can search and arrange by year, studio, star(s) or other fields of data I have entered. I have the slides stored in files originally used for index cards, not unlike the old card catalog files in libraries. As time permits I add more informational data, to the computer, as I find it. New cast or crew names, dates of release, or reviews, synopsis information… whatever I can find, that might aid in future reference.

Like most collectors, I search high and low, and go to just about any length to acquire new slides. I look online, garage sales, flea markets, word of mouth. Sometimes these are dead ends, and other times gold mines. Sometimes, a slide is cheap, many times nowadays, more expensive, because slides have become a craze amongst certain collectors. When I began my accidental collecting – most people were not interested in the small rectangles of glass, or even silent films, for that matter. They were more an item of the seasoned and experienced collector. Now, more than ever, it’s becoming as they used to say in the Twenties, I believe, “All the Rage!”

So, now that you know a little history about the evolution of “Coming Attraction” slides as they pertain to the movies and their exhibition and collecting. Sit back, in your favorite chair, grab some popcorn, maybe a soda, and enjoy a few of the many slides from my collection, and we’ll see you soon, “at the ‘silent’ movies.”